Aby Warburg and Walter Benjamin are two highly anomalous figures within the European cultural landscape of the early twentieth century. It is precisely because of their anomaly that their thinking and works have proved so fruitful and full of meaning, anticipating contemporary practices and methodologies. Today, their critical attitude and research methodology offer interesting points of reflection on the disciplines and practices that revolve around the figure of the contemporary designer.

The archivist

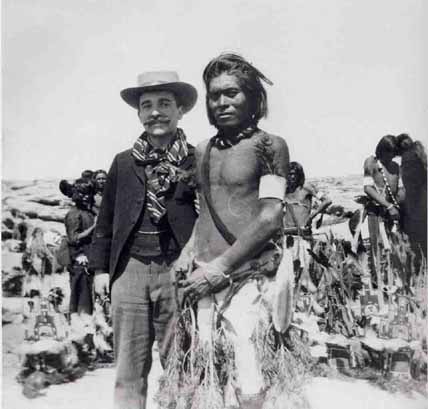

- Aby Warburg (on the left) during his trip in New Mexico, 1896

Aby Warburg (1866 – 1929) was born in Hamburg, the eldest son of a wealthy family of German Jewish bankers. Legend has it that at thirteen he traded his birthright with his brother Max, in return that Max would buy all the books Aby needed during his lifetime. And so Warburg devoted himself against his father’s wishes to the study of art history, coming to collect tens of thousands of works in his library along with an endless collection of photographs.

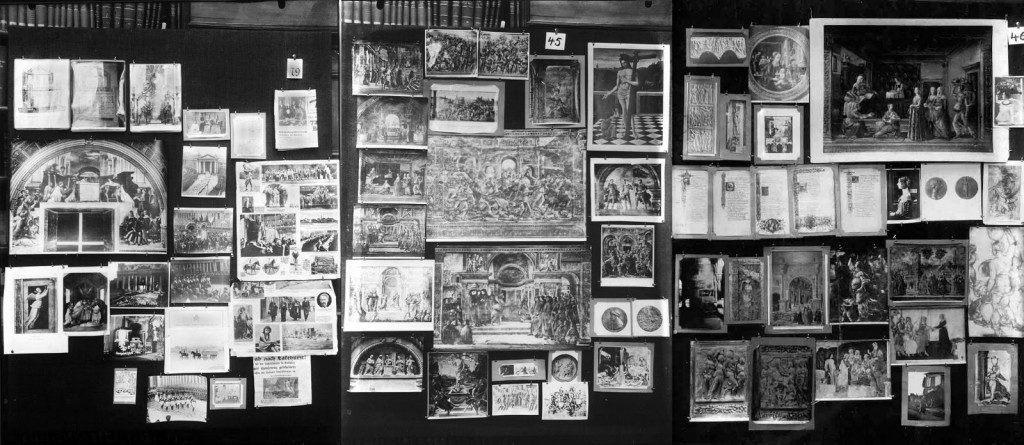

The activity of archivist and historian soon distinguished Warburg from the traditional canon. The innovative aspects of his work are to be sought in the order and organization that Warburg applied to his collection, in which he developed a new way of looking at and interpreting the production of visual representations. These innovations found expression in his main work (left unfinished), Mnemosyne: forty panels in which more than 1,000 images – photographs and engravings taken from books, catalogs, magazines and newspapers – are juxtaposed with each other in a revolutionary way with respect to the tradition of art history. Instead of being sorted and matched according to alphabetical or chronological sequence, the books and images followed cultural and thematic variables; a stylistic and expressive affinity only intelligible through great effort of interpretation. Mnemosyne is a circular and synchronic organization of material similar in many aspects to the modern practice of montage.

- Mnemosyne panels 19, 45 and 46

And so it is no wonder if within a panel of Mnemosyne, images of sacred art and advertising clippings or photos from the newspaper are shown side by side. The affinity which emerged between the diverse figures not only justified the risky approach, but opened the door to a new way of looking at visual material, anticipating by several decades the practice of situationist détournement and, by nearly a century, channel hopping or surfing the web.

If today we are able to recognize in the language of advertising the same mythical power that permeates the sacred images of over two thousand years ago – and if we are able to judge and evaluate the different meanings of that language – we owe it to Warburg and his revolutionary way of extricating from the chaos of visual representations and understanding the archive as an active tool in the construction of meanings and intersecting viewpoints.

The explorer

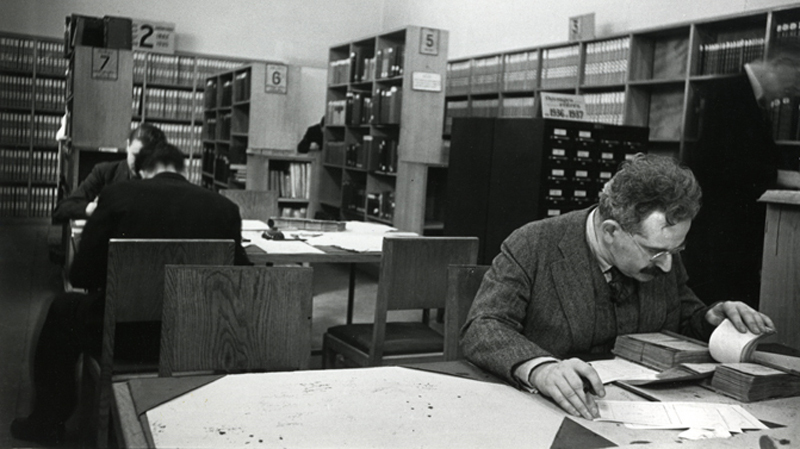

- Walter Benjamin at the Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris, 1937

Walter Benjamin (1892 – 1940), like Warburg, devoted many years of his life to an impressive and ambitious work, both obscure and difficult to understand: Das Passagen-werk. Left incomplete and published posthumously, Das Passagen-werk shares Mnemosyne’s structure – or rather, non-structure – a mosaic, in which thousands of quotes, anecdotes, aphorisms, excerpts from newspapers or advertising, and small philosophical and literary excursus intersect and overlap in an attempt to remap the Paris of the nineteenth century, allegory of the modern era. The Paris of Baudelaire, prostitutes, gamblers, the bourgeois collector, the great universal exhibitions, the flâneur, the passages in which commodities for the first time are offered in a spectacular form and spectacularized; these are some of the images in which Benjamin stumbles during what looks more like the wandering of a drunk, than the expert recognition of an explorer.

However, already in a text written many years before, Benjamin declared how the two things – wandering and exploring – go hand in hand: “Not to find one’s way around a city does not mean much. But to lose one’s way in a city, as one loses one’s way in a forest, requires some schooling. Street names must speak to the urban wanderer like the snapping of dry twigs, and little streets in the heart of the city must reflect the times of day, for him, as clearly as a mountain valley.” Disorientation then becomes not only a positive condition, but essential: to know how to lose oneself in a complex environment loaded with symbolic and allegorical images, like the modern metropolis, may be a necessary experience to find new benchmarks, new crossed paths, oblique, not marked by the guides we receive from tradition. We thus learn a new language, that of “things,” of works, objects, artifacts produced by human labor, an idiom often unknown even to those who build such things, hidden beneath their surface. Not by coincidence was Benjamin among the first to take an interest in advertising – posters, signs, window displays, sandwich boards, newspapers and magazines – and how commodities were able to express themselves through a language in which the expectations, dreams and hopes of a utopian society were glorified, yet at the same time, betrayed.

In this sense, Benjamin may be considered the first true explorer who penetrated into the tumultuous chaos of the modern metropolis – and of modernity – looking for new paths, new shortcuts, new avenues of escape between the windows, posters, lighted and crowded streets and flaunted commodities of the new urban jungle.

The designer

About a century apart, the archivist and the explorer – or rather, the ways in which Warburg and Benjamin redefined these two practices – have proven to be two crucial figures within the contemporary cultural landscape. A landscape characterized by an impasse over the last thirty years due to productive, technological and social intricacies. Some of these cul-de-sac’s can be seen, for example, in the – sterile and useless – contrast between Author and Reader; in the now anachronistic concept of intellectual property and copyright; or in the difficult discussion that revolves around the so-called “immaterial labor”; or still in the gradual disappearance of boundaries between professions. If we consider the designer to be one who gives shape to things, tangible and intangible, in order to form meaning – and not just the graphic designer or product designer, but also artists, illustrators, photographers, architects, urban planners, journalists, writers, directors, stylists – then the figures of the archivist and the explorer are useful in understanding what it means to design today. They help to draw new strategies and escape routes to get out of those blind alleys.

Today production is no longer exclusive to designers. After three decades of the internet, globalization, smartphones and the cloud – thirty years in which production, especially the symbolic production of images, representations and narratives, has been decentralized and diffused in a widespread manner – the designer no longer relies solely on practical and productive activities in order to justify their value in the labor market or to distinguish themselves. A good designer today joins practices and attitudes to the process of production much like the two figures introduced by Warburg and Benjamin: the archivist and the explorer. As the archivist, the designer now finds himself working in an environment flooded with texts, performances, works already in circulation within the cultural market, or which already belong to an imaginary or collective memory. The overproduction of information and media bombardment have forced designers to design new criteria, to select and organize from the immense mass of information – criteria that is mobile, adaptable, temporary, of emergency – just as Warburg organized the texts of his library and visual representations in Mnemosyne. Similarly, the complexity of the contemporary leads the designer to abandon the clothes of the manufacturer and to become something more like an explorer, someone who operates and works not only by creating new objects, new ideas, new narratives, but also by providing new access roads to objects, ideas and already existing narratives, planning paths or systems of guidance able to create a network of connections between meanings and contexts.

Bibliography

Aby Warburg

- Ernst Gombrich, Aby Warburg. Una biografia intellettuale, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1983

- Giorgio Agamben, Aby Warburg e la scienza senza nome, in G. Agamben, La potenza del pensiero, Neri Pozza, Vicenza, 2010

- Kurt W. Forster, Katia Mazzucco, Introduzione ad Aby Warburg e all’Atlante della Memoria, Bruno Mondadori, Milano, 2002

- http://www.engramma.it/eOS2/atlante/

Walter Benjamin

- Walter Benjamin in Rolf Tiedemann (a cura di), Opere complete – Vol. IX – I “passages” di Parigi, edizione italiana a cura di Enrico Ganni, Einaudi, Torino, 2000

- Walter Benjamin in Renato Solmi (a cura di), Angelus Novus, Einaudi, Torino, 2006

- Walter Benjamin, L’opera d’arte nell’epoca della sua riproducibilità tecnica, Einaudi, Torino, 2000

- Walter Benjamin, Infanzia berlinese intorno al Millenovecento, Einaudi, Torino, 2007

Postproduction and design

- Jon Sueda, All possible future, Bedford Press, London, 2014

- Andrew Blauvelt, Ellen Lupton, Graphic Design: Now in Production, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 2011

- Nicolas Bourriaud, Postproduction. Come l’arte riprogramma il mondo, Postmedia Books, Milano, 2005

- Riccardo Falcinelli, Critica portatile al visual design, Einaudi, Torino, 2014